White flags, yellow hearts, and the birth of COVID memorial

A new visual language has emerged for pandemic grief and remembrance

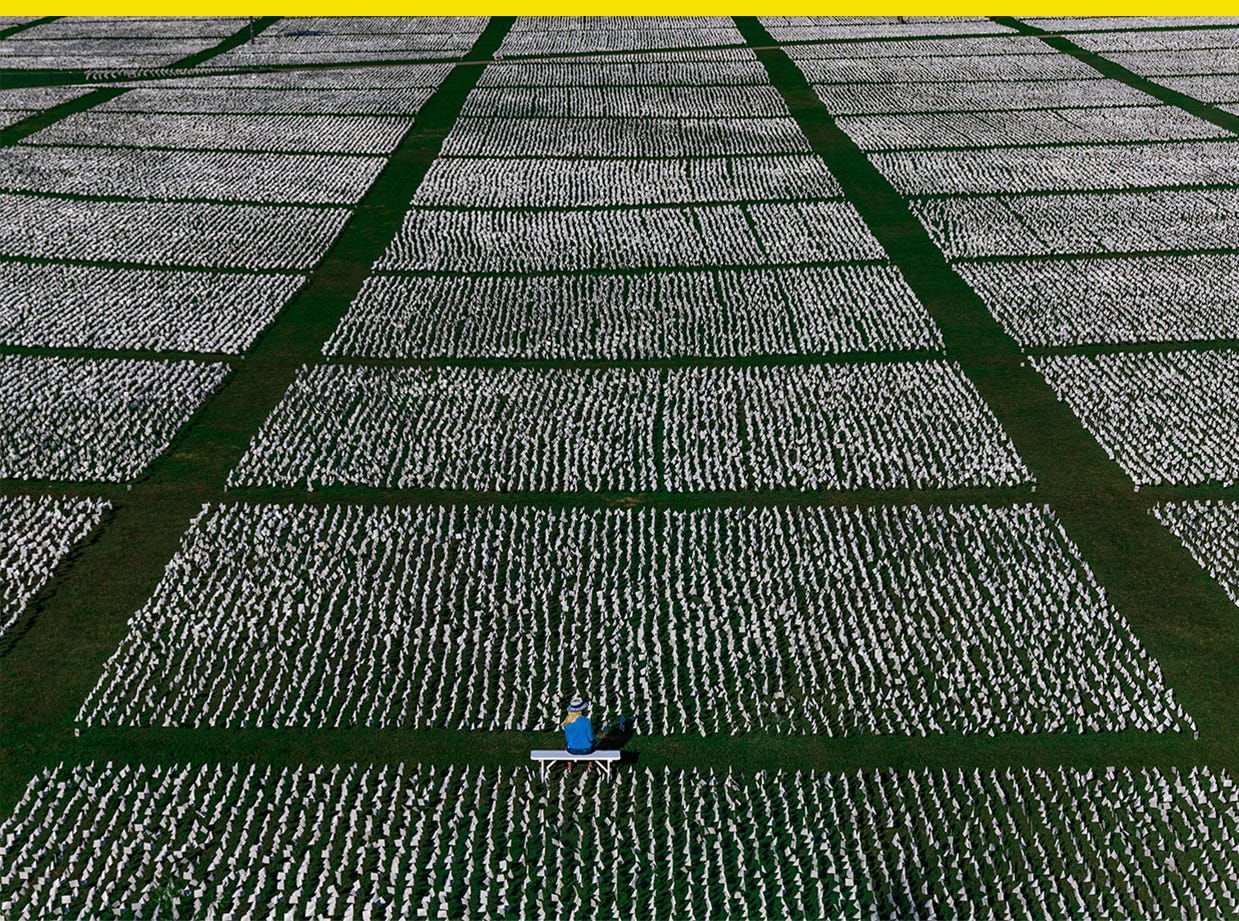

It was overcast and sprinkling the day In America: Remember opened on the National Mall in September. Artist Suzanne Brennan Firstenberg’s installation included small white flags for the 670,032 Americans who had so far died from COVID-19, and I came to experience opening day for myself and place a flag for my dad, who died from COVID in February.

Standing at an entrance for the exhibition and facing towards the Lincoln Monument, the flags looked like they went on forever. It felt like a gut punch. The vastness of the flags let me see and feel the enormity of the pandemic’s death toll in a way numbers and charts never could, and it took my breath away.

Spread across 20 acres, the scale of our loss of life was laid out in the shadow of our national monuments, the largest participatory public art exhibition on the Mall since the AIDS quilt in 1996. All at once, it was art, a mid-crisis memorial, and a powerful piece of data visualization for a death toll that’s grown mind numbingly high. Firstenberg hoped visitors would look at one flag and imagine the loss that one person’s death meant to their family and community, and then lift their gaze.

“We made grief viewable,” she told me. “We made it visual.”

We often turn to symbols to represent loss or raise awareness in the midst and aftermath of public health crises, like pink ribbons for breast cancer and red ribbons for AIDS. For COVID, white flags and yellow hearts have become symbols to memorialize and grieve.

The yellow heart was first used in the UK early in the pandemic. David Gompertz lost his wife Sheila to the virus in April 2020, and he wanted a way to share grief with others who lost a loved one, even as the country was in lockdown. Inspired by the tradition of tying yellow ribbons around trees, a yellow heart could be placed in windows or used online. Today it’s used in social media profiles of people who lost someone to COVID and by COVID organizations, but it’s meant for anyone who “lost someone during this time, not necessarily from COVID-19,” Gompertz’s granddaughter Becky wrote for Marie Curie. The yellow heart is a symbol of remembrance and a way of letting people know you’re grieving, she said.

After losing her mother Mary Castro to COVID-19 last year, Rosie Davis organized the Yellow Heart Memorial in Irving, Texas, with help from Hannah Ernst, who lost her grandfather Cal Schoenfeld to the virus. Ernst created yellow heart portraits that went on display at the Irving Archives and Museum, and she told NBC 5 in Dallas she thought the artwork was “a little more impactful than just seeing the constant reminder of the numbers on TV.” Yellow Heart Memorials have since been held across the country, from Denver and New York City to Simi Valley, Calif., and Morristown, Ind.

The yellow heart is used used to “brighten up a tweet or message,” or as a bit of color “to make you smile,” according to Emojipedia. Cosmopolitan’s guide to using heart emoji says the yellow heart has “gentle” energy, and that it’s best used for situations like “new relationships where you want to show affection without fear of coming on too strong or when you’re sending to family members.”

“You find that yellow is a color that’s venerated around the world by many societies,” said Leatrice Eiseman, executive director of the Pantone Color Institute. “If you do color word association studies, as we have done at Pantone, every culture almost invariably, when you show them the yellow swatch, like an Illuminating Yellow, they’ll come back with ‘sunlight,’ ‘happiness,’ ‘cheer,’ ‘love,’ ‘family,’ ‘embracing,’ those kinds of very positive feelings around the color.”

A yellow heart is welcoming, warm, and happy, and it’s for everyone. It’s everything you could want from a heart.

The white flag was chosen in part because of its affordability.

“I had to find something I could afford a quarter of a million of,” Firstenberg said of her first version of In America, put on display in the fall of 2020 near Washington’s RFK stadium with nearly 270,000 flags for the death count at the time.

Small white flags were within her budget, but they were also reverential. There’s a solemness to hundreds of thousands of white flags laid out in rows, like headstones at Arlington National Cemetery, and the breeze gives them life. “They have a physicality,” Firstenberg said. My favorite moments in the installation were when it was quiet and all you could hear was the rustling of the flags. It felt holy.

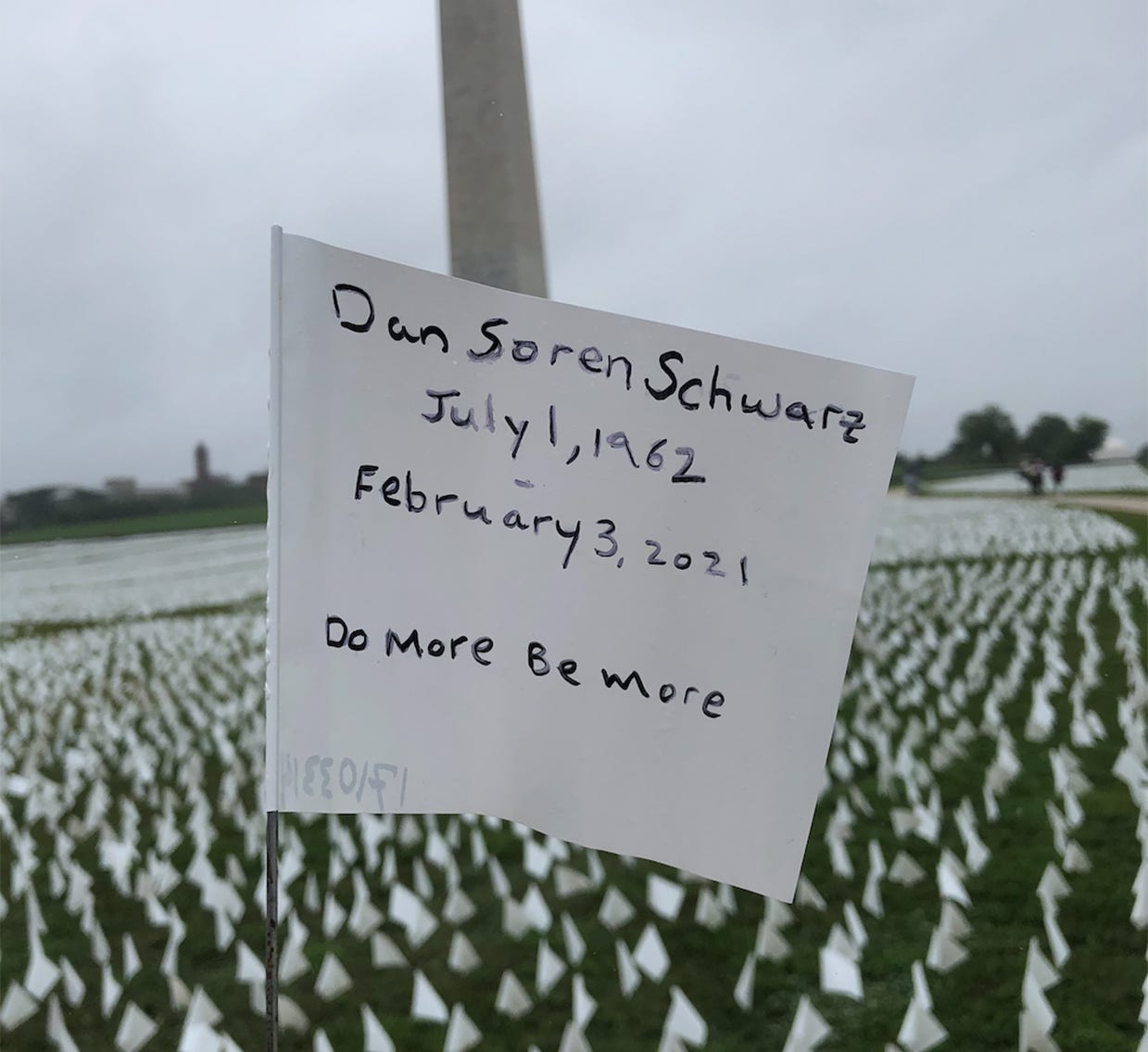

Those who lost someone to COVID were invited to dedicate a flag by writing a message and placing it on the Mall. Those who couldn’t visit in person could submit a message online for volunteers to fill out, and the flags were geotagged and made viewable in an online version of the installation. Firstenberg estimates at least 16,000 flags were dedicated by the end of the exhibition, but she’s still in the process of cleaning and archiving them now.

In America: Remember included signage that counted the dead, and next to it was a small plot of 27 flags to represent the cumulative death count at the time in New Zealand, which took more proactive public health measures against COVID than the U.S. The message that it didn’t have to be this way renders the flags as white flags of surrender in a war on a virus many gave up fighting. By the time the installation closed 17 days later, the U.S. death count had risen by 31,101 additional deaths.

There’s so much to be angry about when it comes to COVID in America. The wickedness of politicians and public figures who lied to the people who trusted them. A rotting political culture that made public health partisan. Social networks infected by misinformation. As of this week, COVID has killed more than 750,000 Americans, more than were killed in the Civil War, our deadliest war. A nation that beat the Nazis and landed men on the moon has been brought to its knees by a microscopic virus.

One of my biggest worries visiting In America: Remember was that I would be angry. That the pandemic has been politicized makes me so mad, but I didn’t want that anger in my heart when I visited. Instead, I found hope in a field of blank white flags and all that was unwritten.

Having the chance to dedicate a flag felt like the chance to write your own story. Some of the flags I saw had messages of sadness — “If we knew the last time we saw you would be the last, we would have hugged longer” — and others read like letters to heaven. “Dad, we are going to be ok.” As I read, I saw people in various stages of mourning, and all of them were right.

There was Reverend Mullins from Oklahoma who was gone but not forgotten, and Diane, the matriarch of her family “taken way too soon.” Next to where I placed my father’s flag were Fannie and her daughter Amaris, who died within a week of each other in Georgia, and Juan, whose loved ones wrote “¡Te recordaremos siempre!” We will always remember you!

“A lot of them are celebrations of life,” said Este Geraghty, chief medical officer at Esri, a location intelligence company that helped geotag the flags. “Some of them break your heart, some of them add to the outrage that this shouldn’t be, and some of them just make you smile.”

For my father’s flag, I wrote a phrase that’s become something of a slogan in my family since he passed. Every Christmas Eve, my family’s tradition is for everyone to write their “gift to Christ” on slips of paper that are put into a box and sealed away. It’s a chance for personal reflection, and it’s confidential. After my dad died, though, my mom dug up his slip of paper, where he had written “do more be more.” It’s a pledge to improvement and progression, a striving for good. I wrote it on my dad’s flag, along with his name, birth, and death dates, and planted it with a prayer in my heart. We will never forget those we’ve lost. May we defeat this virus and build a better world in their memory, amen.

White flags and yellow hearts are part of a new visual language for a movement that’s large and sadly continues to grow. For every COVID death, approximately nine surviving family members are impacted, according to research from Penn State, and in the years to come, many will use white flags, yellow hearts, and other symbols to grieve, remember, and say what words and numbers can’t.

Born in 2020, these symbols will take on new life in 2022 and beyond. Yellow Heart Memorial encourages people to host memorials in their own communities, as does Firstenberg, who’s working on a traveling exhibition of dedicated flags. In March, we’ll commemorate COVID-19 Victims and Survivors Memorial Day, a proposed holiday I hope can become a day for peace.

It took three days to deinstall In America: Remember, and it left the Mall checkered with squares of green grass and a yellowed grid worn down by visitors who walked the installation’s hallowed paths. The Mall was marked by COVID, to borrow a phrase from the COVID justice advocacy group, and it made me think of the mark this virus will leave on all of us long after the pandemic ends, whether or not we lost someone. So many have suffered and there’s no shortage of people in need and good that needs to be done.

The pandemic has forced us all to question what we value, and I wonder if a nation can’t do the same. Recovering from grief or trauma is a long and difficult process, but it offers the chance for post-traumatic growth, like a greater appreciation for life, or an unshakable confidence.

We can come away from this experience and continue on with our cold uncivil war, or we can bind up this nation’s wounds, as Lincoln said, with malice toward none and charity for all, so that we may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

A once-in-a-century plague is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to reconsider our path, and the choice is ours. We get to write our own story. 🏳️💛

What a beautiful piece of journalism, Hunter. So glad to see you back with Yello.