What we can learn from Jimmy Carter’s revolutionary nice-guy campaign

Plus: What the FDA’s redesigned rules around “healthy” food labels means for packaging

Hello, in this issue we’ll look at what politicians can take from Jimmy Carter’s first-of-its-kind modern media campaigns and the how the FDA’s updated rules about healthy food will show up on packaging.

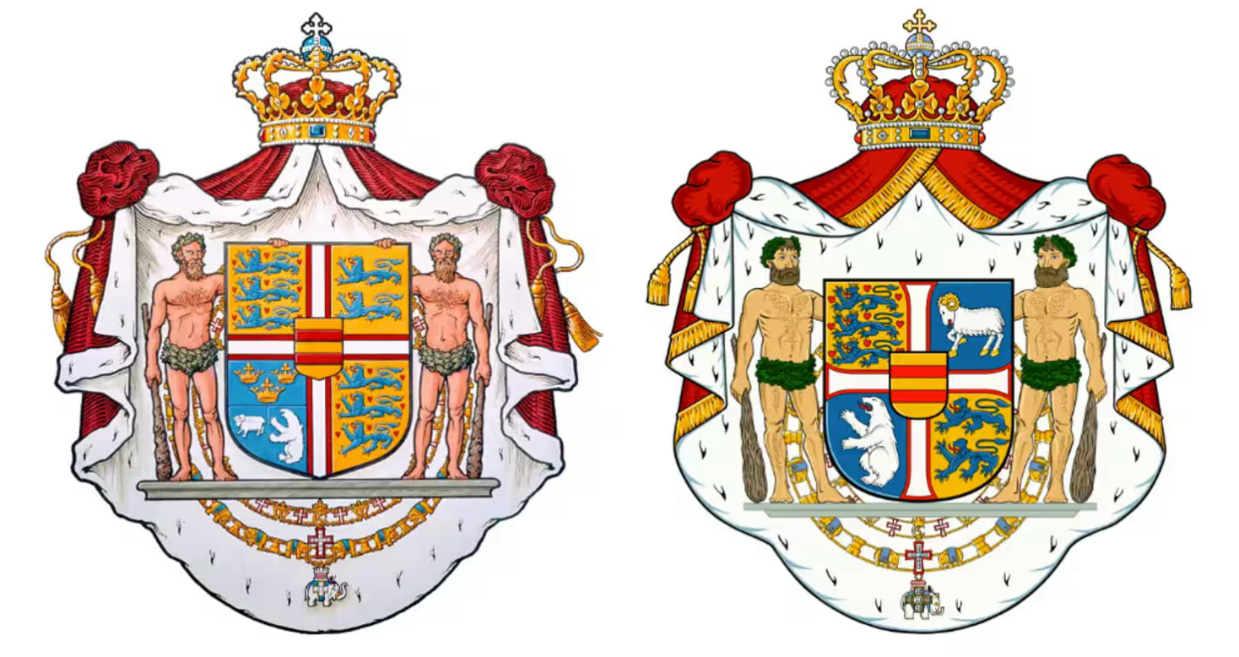

Scroll to the end to see: the tweak one country made to its coat of arms following Trump’s comments about U.S. expansion 🐏

What we can learn from Jimmy Carter’s revolutionary nice-guy campaign

Presidential campaigns these days look for ways to bypass the media, using social networks and podcasts to get their message out directly. In the Bicentennial Campaign of 1976, the then-former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter did just the opposite.

Carter was the right man with the right message for the right moment for the first presidential campaign after Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace, but the peanut farmer and Sunday School teacher had to reimagine what running for president looked like in a new era. Post-Watergate reforms designed to limit money’s influence in politics meant candidates couldn’t rely on advertising to the same extent they had in recent campaigns, and public financing meant candidates were leery of running negative ads since they were using public funds. So instead, Carter ran a media-focused campaign to earn free coverage and he filmed ads designed to communicate authenticity.

A relative unknown at the time, Carter used early television appearances to build his national profile before running for president, like a 1973 appearance on the game show What’s My Line. As part of his publishing agreement for his 1975 book Why Not the Best, he negotiated with his publisher to run full-page ads in newspapers and magazines instead of earning royalties. When he announced his campaign, he did so in front of the press at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C.

“I think we have a nation that is truly great,” he said during an appearance on Meet the Press days after announcing his campaign. “Not that used to be great or someday will be great again.”

Carter courted primary voters as aggressively as he did national reporters, newspaper editorial boards, and local media in the early days of his campaign. The strategy was crucial to raising his name ID and giving his underdog candidacy legitimacy, according to Amber Roessner’s excellent Jimmy Carter and the Birth of the Marathon Media Campaign. The day after he won the Iowa caucus following months of heavy campaigning in the state, he was off to New York to appear on TV shows, now dubbed the “front runner.”

Unlike the slickly produced ads Nixon used to win the presidency four and eight years earlier, many of Carter’s ads showed him speaking straight to camera outdoors while dressed down in work shirts instead of wearing a suit and tie. Presidential campaign ads had never been so informal. Others went documentary-style with B-roll of Carter on his farm or shaking hands with voters to reinforce his image as a man of the people over narration that Carter would be a president who brought honesty and transparency back to government.

After winning the Democratic primary, Carter headed back to his hometown, paused campaign activities until Labor Day, and invited reporters to meet him in Plains. “Carter’s campaign exploited free media to provide American audiences with images of a God-fearing man teaching Sunday school lessons at Plains Baptist Church, a regular fun-loving Jimmy playing softball, a family man hosting a communal fish fry, and a president-in-waiting in training session with foreign policy and domestic affairs experts,” Roessner, the author, writes.

Carter’s campaign couldn’t be replicated today, not exactly. The media attention he sought was possible thanks to a less fractured landscape and the relatively high esteem the press was held in after the Washington Post’s dogged reporting toppled a corrupt presidency (reporting on a crooked White House used to mean something in this country). Still, there are valuable lessons to glean.

Carter’s strategy relied on his image and message being the same across paid and unpaid media. His campaign worked to make sure there was no daylight between what Carter the candidate said and what voters read and saw reported about him in the press. The picture matched the sound.

“If I ever lie to you, if I ever make a misleading statement, don’t vote for me,” Carter said. “I would not deserve to be your president.”

For candidates with an eye to replacing President-elect Donald Trump in 2029 with a modern version of Carter’s playbook, the details will be different but the guiding principles should be the same. To reach a cynical electorate, a unified, honest, positive message needs to be multi-platform.

Previously, in YELLO:

What the FDA’s redesigned rules around “healthy” food labels means for packaging

Food brands will now have to do away with at least one form of deceptive communication design. According to a new rule by the Food and Drug Administration, they’ll have to get rid of misleading “healthy” labels on packaging, unless the product meets criteria indicating that it actually is good for you.

The decision puts a deceptive label to rest, and offers an example of how to make packaging easier to interpret for consumers navigating the grocery aisle. Brands are supposedly all about authenticity and trust of late, but it seems sometimes the long arm of the law needs to force their hand. However, some experts say the label rule, which goes into effect on February 25, doesn’t go far enough.

Labels are an integral part of modern food packaging, from black-and-white Nutrition Facts charts to simple symbols for recyclability and country of origin. These graphics are a bit of communication design meant to inform, but it’s not clear consumers always understand what they see.

Under the new criteria, packaging can use the term “healthy” only if the product contains a certain amount of at least one of the food groups recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans—including fruits, vegetables, grains, fat-free and low-fat dairy, and protein—and doesn’t surpass limits on added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium.

These thresholds vary by food type, and it means foods like fortified white bread and many sugary yogurts and cereals that could once be classified as “healthy” can no longer be (sorry, Chobani). Additionally, the new rules automatically qualify certain nutrient-dense foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, seafood, eggs, and nuts for healthy labeling if they contain no additional ingredients except water.

The FDA is also developing a standardized “healthy” symbol that food manufacturers could use on their packaging if their products meet the criteria.

The new guidance “is a step in the right direction,” Alice Lichtenstein, a Tufts University professor of nutrition science and policy, tells me in an email, but for it to be effective, “the general public needs to be educated in its existence and how best to use it.” That’s not dissimilar to the standard for any new design system.

The new rules address the policy gap on sugary foods that were previously labeled healthy but shouldn’t have been, and accommodates for “good fats” as well as concerns about ultra-processed foods. But even these changes are “just a drop in the bucket compared to all the challenges that remain in making food labels useful for deciding if foods are healthy or not,” says Xaq Frohlich, an Auburn University history associate professor and author of From Label to Table: Regulating Food in America in the Information Age.

“Despite decades of using food labels as a policy solution to public health problems, America’s health problems persist,” Frohlich adds. “I believe this is because the FDA needs to do more than just tweak labeling rules in order to improve the nation’s food markets and the rampant misinformation in them that confuses consumers.”

The FDA says data shows a majority of Americans’ diets exceed the current recommendations for saturated fats, added sugars, and sodium, and that the dietary patterns of 79% of Americans are low in dairy, fruits, and vegetables.

Jim Jones, FDA deputy commissioner for human foods, sounded hopeful about the new labeling guidance, noting in a statement that the new rules may “help foster a healthier food supply if manufacturers choose to reformulate their products to meet the new definition. There’s an opportunity here for industry and others to join us in making ‘healthy’ a ubiquitous, quick signal to help people more easily build nutritious diets.”

Have you seen this?

Patriotism is out of style, at least when it comes to logo design. Since the 1960s, the use of U.S.-shaped logos has fallen by 88%. Brands are also moving away from terms like “American.” [Fast Company]

Danish king changes coat of arms amid row with Trump over Greenland. For 500 years, previous Danish royal coats of arms have featured three crowns, the symbol of the Kalmar Union between Denmark, Norway and Sweden. But in the updated version, the crowns have been removed and replaced with a more prominent polar bear and ram to symbolise Greenland and the Faroe Islands respectively. [The Guardian]

How Mark Zuckerberg pivoted Meta to the right. In recent months, CEO Mark Zuckerberg has made a series of specific moves to signal that Meta may embrace a more conservative administration. [NBC News]

History of political design

Jimmy Carter for President poster (1976). Carter White House Communications Director Gerald Rafshoon told UVA’s Miller Center that despite speculation Carter’s campaign used the color green because it tested positively for “naturalness,” “The reason it was green was that in 1970 [when Carter ran for governor], the day I had to come up with a brochure and graphics of it, green was the only paper in the agency at that time. They asked, ‘Why is it green?’ I said, ‘What’s your favorite color?’ Somebody said, ‘Blue.’ And I said, ‘Well, if you had my job, it would be blue. I like green.’” R.I.P. Jimmy Carter 🥜💚

A portion of this newsletter was first published in Fast Company.

Like what you see? Subscribe for more:

That nice doesn’t = capable?