What we can learn from George Romney’s campaign to reach across the aisle

George Romney and the ticket-splitters

The 1964 election was held less than a year after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and Democrats won in a landslide. Incumbent President Lyndon Johnson went 486-52 that year in the Electoral College over Sen. Barry Goldwater (R-Ariz.) in a race defined by fear over Goldwater’s extremism and the threat of nuclear war, and Democrats not only kept the House and Senate, they grew their majorities in both.

In Michigan, though, one Republican defied the blue wave against the odds.

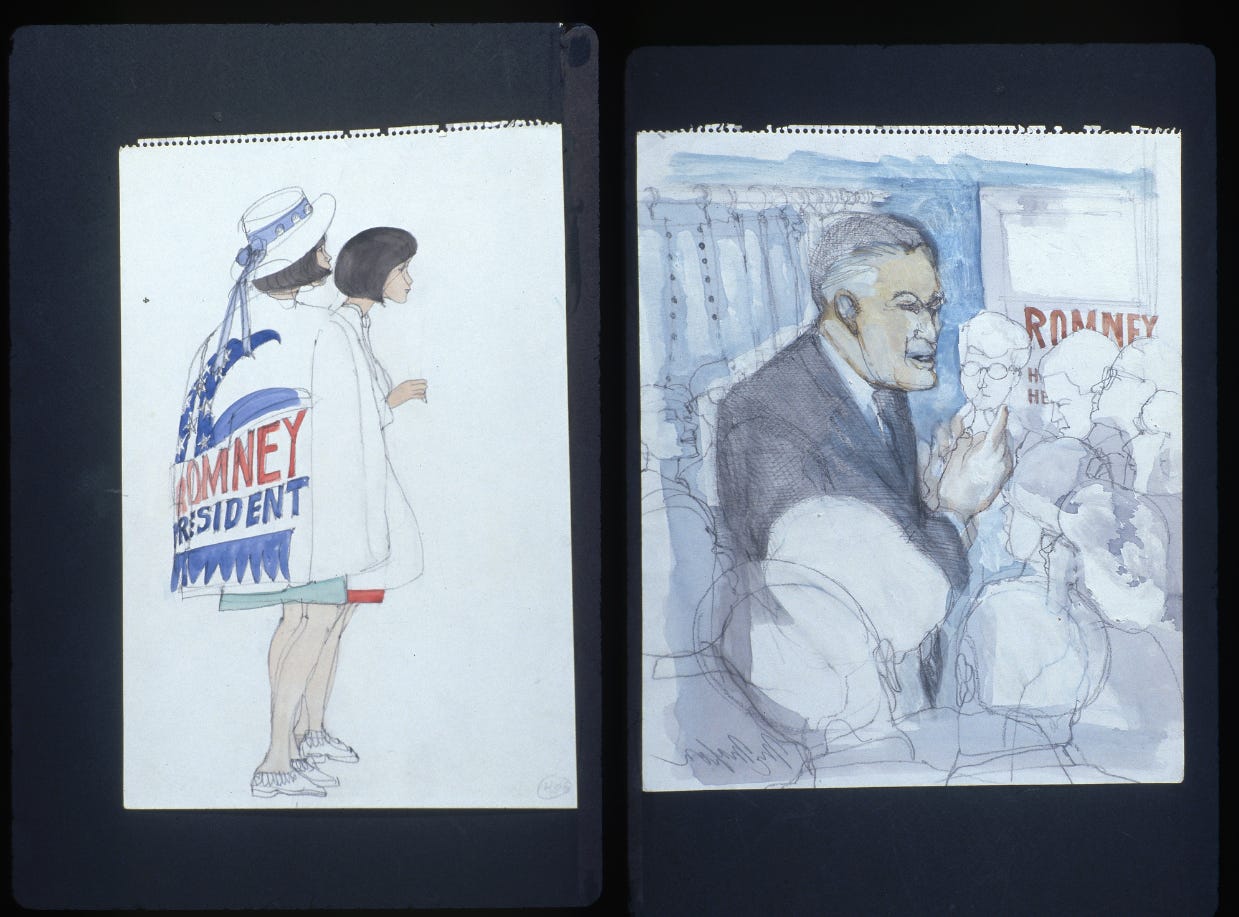

Michigan Gov. George Romney (R) was the former president of American Motors Corporation and the father of 2012 presidential candidate and former Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah). He ran for governor three times in Michigan and improved on his performance every time. He won more than 51% of the vote in 1962, more than 55% of the vote in 1964 (the year of Johnson’s landslide), and more than 60% in 1966.

Romney’s record in Michigan, where the trees are the right height, is all the more impressive considering the state’s voting machines were stacked against him by design. To vote single ticket in Michigan at the time, voters only had to pull one lever, while to vote across party lines required voters pull each individual lever for their candidates of choice. It was easier to vote straight ticket, but in 1964, when Johnson won Michigan by a two-to-one ratio, Romney still held his seat. His secret was the split-ticket voter.

The ticket-splitters

Romney’s first foray into politics came after heading the constitutional convention to rewrite Michigan’s constitution in 1961. There he met Walter de Vries, a man who ran as a delegate for the Democratic and Republican state conventions and was elected to both. That appealed to Romney, who considered the liberal-conservative divide of his time to be an outdated relic of an earlier era, according to biographer T. George Harris.

When Romney decided to run for Michigan governor the following year, de Vries became his director of research and strategy, and he faced a challenging task. No Republican had won a gubernatorial race in the state in 14 years, and to win, Romney would need to sweep Republicans, win two-thirds of independents, and convince enough Democrats to cross party lines. He had to build a cross-party coalition, it was the only way.

De Vries got to work, pouring over voting behavior research data to find voters who weren’t Republican but might be convinced to vote for Romney. He and his team found these “ticket-splitters,” and after lining up their findings with Census data, they located where these voters lived and volunteers started knocking doors.

Romney’s campaign contacted nearly twice as many of these voters as his Democratic opponent did, and when Romney canvassers came across undecided voters while knocking, they wrote down why they were undecided. These voters would later receive a hand-signed letter from Romney himself explaining where he stood on the issue they were concerned about and asking for their support.

Romney’s split-ticket voters read newspapers, watched TV, and listened to radio, and they were more likely to meet candidates in person than single-party voters. They were engaged. So to reach them, Romney’s campaign started airing soft-sell ads early on, introducing voters to the candidate earlier in their decision-making process rather than rely on running ads in saturation in the closing weeks of the campaign.

“The ticket-splitter did not emerge from our data as a one-issue person or as a voter who could be easily reached by highly emotional appeals,” de Vries wrote in his book The Ticket-Splitter. “Rather, he emerged as a complex voter who had a ready grasp of the campaign issues and who was oriented toward problem-solving by candidates rather than by political parties.”

Romney’s strategy was “rational and unorthodox,” for the time, de Vries said, but Romney’s string of wins prove that it worked. He appealed to people frustrated by the two-party system.

“There’s nothing more powerful than a coalition of concerned, informed citizens who have cast aside partisan and economic interests and are in agreement as to what ought to be done,” Romney said.

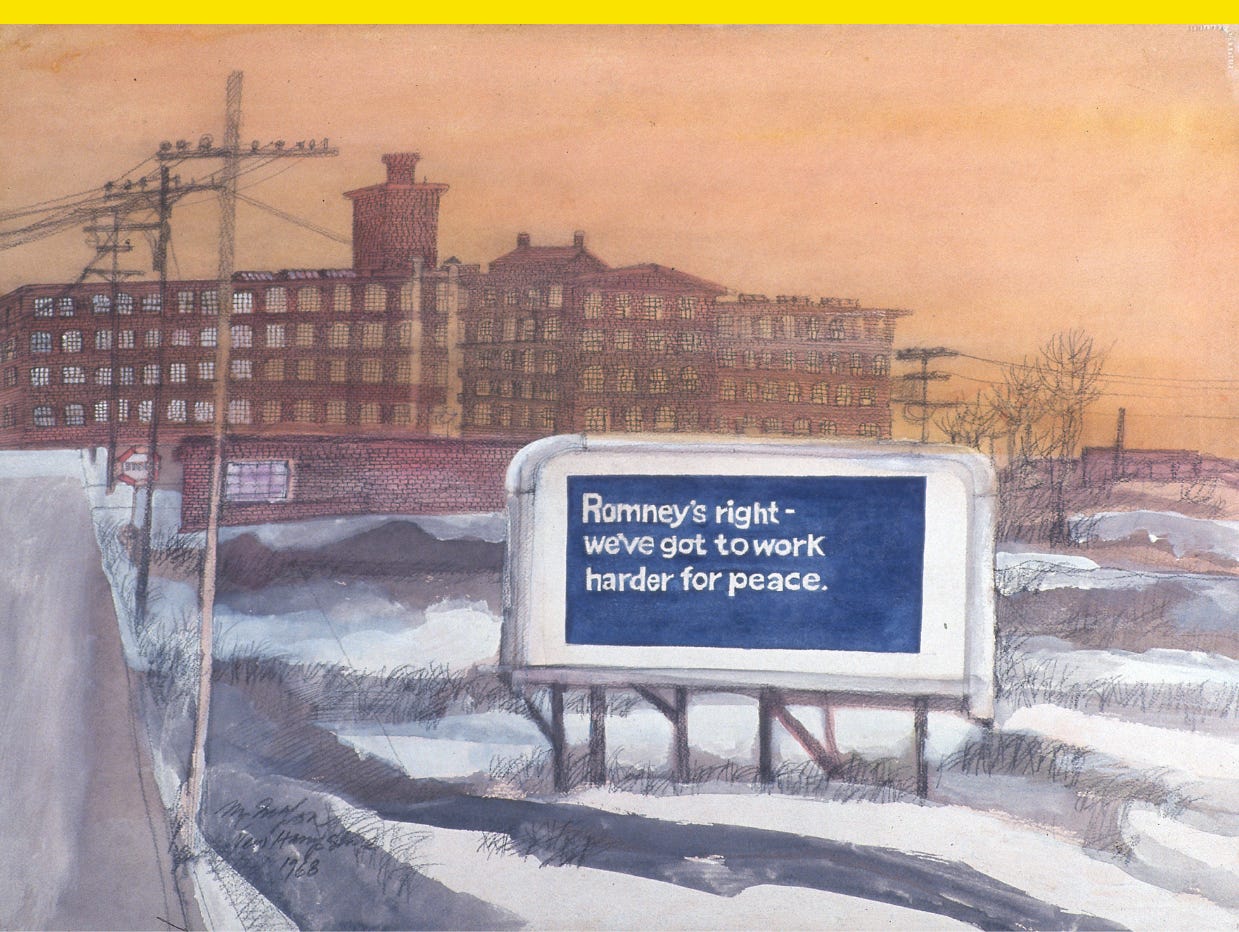

We’ve got to work harder for peace

Though he ran for president in 1968, Romney didn’t much have the chance to test his ticket-splitter strategy on a national level because he dropped out early after making a comment about feeling brainwashed about war. Romney said officials gave him “the greatest brainwashing that anyone can get” when he visited Vietnam. “They've changed their story in Saigon since I was there,” he said. His brainwash comment was seen as a gaffe and he tanked in the polls, but Romney was right.

The campaign when Romney defied the blue wave in 1964 was one marked by extremism, paranoia, and fear. “These are the stakes: to make a world in which all of God's children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die,” Johnson said in the voice over of the year’s most famous ad.

The stakes can feel just as high today, but Romney showed a different way. He won by building bridges instead of fear mongering, peace instead of war. We must love each other or we must die. We’ve got to work harder for peace.

All of us must be loud and clear. There was widespread, bipartisan condemnation of Charlie Kirk’s assassination in Utah last week. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) tied the condemnation of political violence to the broader defense of democracy: “[I]f we honestly believe in democracy, if we believe in freedom, all of us must be loud and clear: political violence, regardless of ideology, is not the answer and must be condemned.” [Whig by Hunter Schwarz]

Where the trees are the right height — my rose for the day