If you gaze at politics' A.I. future, it gazes back at you

What the A.I. revolution could mean for politics

The generative artificial intelligence revolution in politics has arrived, but it’s so far relying on earned media.

The Republican National Committee responded to President Joe Biden’s reelection announcement last week with an ad featuring A.I.-generated images. The spot, “Beat Biden,” isn’t airing as an ad on platforms including Meta or Google. Instead, it’s reached more than 260,000 views on the party’s YouTube page, plus countless more through news media coverage.

The ad’s novelty as the first A.I.-generated political spot by a major U.S. party ensured press coverage (like this) and guarantees it will live on as the answer to future trivia questions. Despite the newness of the technology, though, the message of the ad is old. It’s a straightforward attack ad, hitting Biden as weak with visual tropes like crowds of people as the narrator references the border and a closing image of Biden with his head down, as if in disgrace. There’s a computer-generated homeless encampment under an A.I. Golden Gate Bridge and a very hot imaginary MS-13 gang member with a cigarette floating on his lip.

Generative A.I. can be thought of as a cliché generator or a smartphone’s autocomplete scaled to 10,000, said David Karpf, an associate professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University, at a panel I covered in March. Political rhetoric is nothing without its clichés, and in that way, A.I. acts like a mirror, reflecting our political platitudes back at us. If you ask ChatGPT to write political fundraising email copy, it will.

RNC chair Ronna McDaniel told Fox News the A.I. ad was “not a deep fake” because they shared up front that it was generated by A.I., but the spot’s disclaimer — “built entirely with AI imagery” — is hard to read and small enough that Fox News’ own “political ad” label covered it up during the segment.

For the American Association of Political Consultants, or AAPC, such a disclaimer doesn’t cut it. The nonpartisan group said Wednesday it condemns the use of deceptive generative A.I. content in political campaigns and that “deep fake” content violates its code of ethics. Disclaimers and warnings, it said, are insufficient.

“The rise of so-called ‘deep fake’ content generated by A.I. in political campaigns presents a troubling challenge to the free and fair debate of political ideas,” the AAPC said in a statement. “Citizens must have confidence in the basic truthfulness of political campaigns. While the public’s trust in institutions and campaigns has been shaken in recent decades, the use of ‘deep fake’ generative A.I. content is a dramatically different and dangerous threat to democracy.”

The group called on media and advertising platforms to refuse to carry ads with “deep fake” generative A.I. content and said ads made with the technology won’t be eligible for any of its awards.

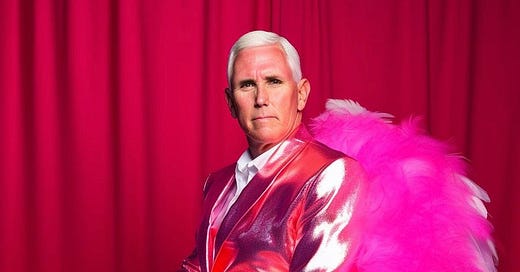

Even if campaigns agree to not use A.I. imagery in their ads, the technology is already part of the political discourse. The single-serve meme account rupublicans posts A.I.-generated images of Republican politicians like former Vice President Mike Pence in drag, and it has more than a quarter of a million followers since first posting in March.

The debate over the role of A.I. in politics is similar to the debate happening in other industries that rely on trust. BuzzFeed, which recently shut down its news division where I once worked (RIP), plans to use A.I. to create content, but CEO Jonah Peretti said the technology was harder to use in the news space. “Journalism needs to have such high, high standards of credibility and trust,” he told Axios. Similarly, Amnesty International removed A.I. images on social media after facing backlash.

It’s impossible to know exactly how artificial intelligence will influence politics and next year’s election, but at a time when anyone can mint an infinite number of Mike Pence drag queens on demand, one wonders if the joke’s effect is diminished, if the proliferation of easy-to-make, computer-generated images devalues the salience of a meme like a market flooded with cheap cash. If no one believes what they see, what then?

Taming the coming visual inflation will take innovation, and at the same time, it presents an opportunity. Anyone can make a Mike Pence drag queen jpeg, but there’s only one living, breathing Mike Hot Pence. A computer cannot love or select all squares with buses or marvel at the majesty of a sunrise and the beauty of a new day. If you prick it, it does not bleed. For all the A.I. revolution threatens to upend, it could very well spur a renewed interest in the human over robots, in what’s real over the artificial.

Have you seen this?

Can good creative win elections? A good logo on its own can win no election; if the most compelling TV ad is seen by no persuadable voter, it changes no one’s mind. Good creative isn’t simply clever or well designed, but if it’s consistent, authentic, and speaks to voter’s needs, it can be the difference between getting your message across to voters or not. [𝘠𝘌𝘓𝘓𝘖]

One of Shepard Fairey’s three original “Hope” portraits is going to auction. “The sale will take place on May 7 at Santa Monica Auction’s two-day Spring Auction, with a starting bid of $500,000 for the original collage.” [The Argonaut]

Artist Plate Project returns for third edition. The series raises money for meals for low-income New Yorkers with plates designed by artists. Virgil Abloh’s “Life Itself” plate was one of his final pieces released before his death in 2021, and the project is back with a black version of the design that’s being released with the support of Abloh’s family. [Hypebeast]

A British couple bought two vases for $10 at a thrift sale. They turned out to be art nouveau collectibles worth 150 times that. “The vases, it turned out, were antiques from around the year 1900, made by Loetz, an art glass manufacturer active in the Bohemia region of Austria-Hungary from 1836 until 1947.” [Artnet News]

Like what you see?

Subscribe for more: