How politicians build partisan brands off their states

Politicians are leaning on their state’s red or blue bona fides to prove their own partisan credentials

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ second inaugural address earlier this month doubled as a conservative infomercial for the Sunshine State. While the state’s tourism corporation promotes beaches and amusement parks, the potential Republican presidential candidate called Florida “a citadel of freedom,” “land of liberty,” and “where woke goes to die.”

Politicians’ home states are an essential part of their biographies and helpful in building recognizable national brands, particularly for ambitious governors like former Georgia peanut farmer Jimmy Carter and one-time Texas Rangers CEO George W. Bush. But increasingly, politicians are leaning on their state’s red or blue bona fides to prove their own partisan credentials. As states become more polarized, it isn’t hard to do.

Florida, a once closely contested battleground, has become increasingly Republican in recent elections, and other states have lost their battleground status, too. In the 1992 presidential election, 32 states were decided by a single-digit percentage, a figure that dropped to 14 by 2020. Today, just 12 states have divided state governments.

In California, Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom won his reelection last year by a similarly wide margin as DeSantis and raised nearly $25 million for his campaign. Without a serious challenger, he spent some of that money outside California on TV ads and billboards after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Billboards in Republican-led states, including Indiana, South Dakota, and Texas, welcomed women to California in need of reproductive healthcare. “Texas doesn’t own your body. You do,” read one billboard showing a woman in handcuffs. Another asked, “Need an abortion? California is ready to help.”

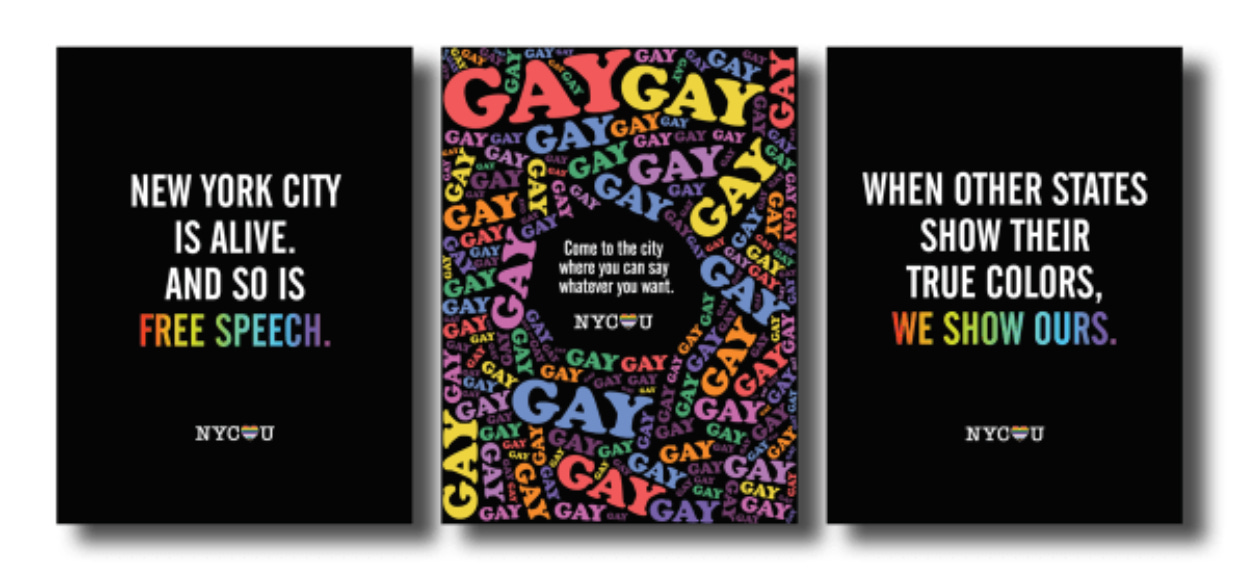

In an email to supporters, Newsom wrote that his campaign was placing the billboards “because I’m privileged to be able to” and “because people like you who support my candidacy support this.” Billboards in Texas might not directly lead to votes in California, but they signaled Newsom’s political values on a national stage to voters back home, something that’s become more common as politics has become more nationalized. After Florida passed its so-called Don’t Say Gay bill, New York City Mayor Eric Adams, a Democrat, announced a billboard campaign in five Florida cities inviting visitors to a city “where you can say whatever you want.”

The rise of states as single-party political actors is more than just ad campaigns. Elected officials in solidly partisan states have grown progressively more combative with the federal government when their party is out of power over issues like public health, immigration, and student loan forgiveness. It’s a trend Marquette University political science chair Paul Nolette traces to Republican attorneys general during former President Barack Obama’s second term, and it’s escalated through the Trump and Biden administrations. Multi-state lawsuits doubled during former President Donald Trump’s four years in office compared to Obama’s eight years.

“There are a lot of political incentives to do this and not a whole lot of downsides because it can help in maintaining and building a statewide profile for a run for Senate or governor,” or even a national profile, Nolette says. Winning the lawsuit is, in some cases, immaterial. “They can say to their fellow Republicans or Democrats, Hey, I’m fighting for you and look at all the ways I’m trying to push back on federal policies that you don’t like.”

Like what you see?

YELLO covers politics, art, branding, and design. Subscribe for more:

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has filed a dozen lawsuits over the Biden administration’s immigration policies, and at last August’s Conservative Political Action Conference, Texas Governor Greg Abbott highlighted the state’s efforts to build its own border wall. “Texas is the only state to build our own border wall to secure our state and to secure our sovereignty,” he said. Supporters who want to help Texas bus migrants to liberal cities can make a donation through the governor’s office.

States are setting their own policies on issues from abortion and gas-powered cars to guns and voting rights. In theory, they’re fulfilling their role as laboratories of democracy—a phrase birthed from a dissent in a 1932 Supreme Court decision over an Oklahoma law requiring a license to sell ice—but research from University of Washington professor Jacob Grumbach found that states increasingly pursue policies that reinforce their dominant politics. Politicians are disincentivized from implementing policies that would improve the other party’s brand, even if other states found it successful, he wrote; and partisan think tanks and lobbying groups do much of the heavy lifting when it comes to policy analysis and bill writing.

While polarized states can give politicians a launching pad for higher office, the 21st century notion of red and blue states betrays the fact that most states are a marbled purple, with expansive rural conservative areas and densely populated liberal cities. What’s good for political brand building isn’t always best for governing, and rather than 50 laboratories for democracy, we’re left with just two: Democratic and Republican.

This story was first published in Fast Company.

Have you seen this?

RIP designer Carin Goldberg. Wrote Michael Bierut, “Carin Goldberg was not a networker. She didn’t talk about ‘design thinking’ or make claims about design’s importance to the corporate bottom line. She simply did beautiful, original, courageous work, day after day, year after year.” Read her 2015 interview with the Cut about designing the cover of Madonna’s self-titled debut album here.

Google is seeking to dismiss an RNC lawsuit accusing the them of bias. Google filed a motion to dismiss a Republican National Committee lawsuit Monday that claimed the email provider marked their campaign messages as spam. [Axios]

Here’s Arizona’s first 2024 U.S. Senate campaign logo. Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-Ariz.) announced Monday he’s running for Sen. Kyrsten Sinema’s (I-Ariz.) seat, setting up the possibility of a three-way race if she seeks reelection. Gallego used blue and green in his logo and Sinema’s 2018 logo was purple and yellow, so Arizona could see some colorful intersections next year.

What if social media algorithms were bipartisan? Facebook and Twitter posts about political out-groups are shared about twice as often as posts about in-groups, but what if social media algorithms didn’t reward that kind of content? [𝘠𝘌𝘓𝘓𝘖]